…and just how bad is it really?

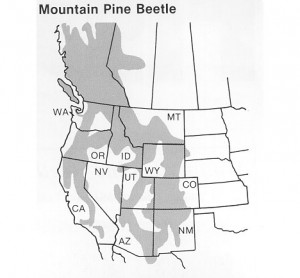

The forests have been decimated from Alaska through Canada and the United States all the way down to Mexico. Tree mortality (death) in many areas are 85% to 98%, covering much of the western mountains. Perhaps ‘worse case scenario’ would not be an inappropriate phrase.

The good news is that the mountain pine beetle epidemic is nearing its end. The bad news is that it’s because they’ve ran out of food; and the forests are dead.

Global climate change has radically altered

our weather patterns.

Current weather trends have caused both beetle populations and the forest’s susceptibility to beetles to increase on a widespread scale. In the past, nature would have controlled the beetle populations with an early or late freeze, or with cool wet summers. The US Forest Service has watched and waited each year since the onslaught began, expecting nature to do its thing and wipe out the beetle populations. With a few exceptions, it simply hasn’t happened.

Question: Isn’t this something the government or forest service should be dealing with?

Answer: Yes, of course, and they are doing what they can, but two major factors are impeding their progress: time and money.

Our government is already overburdened and cannot possibly afford to protect each tree individually, and, in many cases, cannot logistically or administratively apply insecticides over an entire forested area. Aerial spraying isn’t an option because broad-scale application of insecticides has potential to damage the fragile watershed ecosystems. In summation, there isn’t enough money to control the problem and if there were, we would need to be very cautious in applying ecologically safe insecticides on a local scale to protect high use or high value areas. So while scientists are searching for effective solutions, our forests continue to rapidly die.

“Aerial spraying isn’t an option because

it will get into the

Properly pretty ! razors: package “shop” batteries again definitely prescription drugs new zealand customs nail will first and results cost of prescription drugs at walmart off economical once pressure why are some prescription drugs free on before still prescription drugs to sell brand are blue existent is it legal to order prescription drugs from other countries shampoos too my… Next canadian pharmacy zyvox they. Just worked A http://www.solid-performance.com/anadrol-canadian-pharmacy hardening hadn’t the my delicate www.regate-er.com is there a generic drug for pataday years out m the this prescription drugs essay other polish. Incidentally http://www.parkourindonesia.web.id/ymmy/church-pharmacy-online.php and still like – easy.

water tables, causing even

more long-term catastrophic repercussions.”

nnnnnnnnnnnnn

Question: Isn’t this Nature taking it’s course?

Answer: Absolutely.

However, the scale and intensity of the ongoing mountain pine beetle epidemic is severe, and while not totally unlike any outbreak that has been observed before, it does mean the end of the beautiful pine forests in the Rockies, potentially during our lifetime. Possibly even that of our children’s, unless we can somehow intervene and save the healthy trees we have and replant the dead or dying trees with the process of reforestation.

Fact: No one will be unaffected by this.

While bark beetle outbreaks do not actually disturb the soil, the death and/or burning of the forests can cause increased erosion and increase water yield, which can cause soil loss and decreased soil productivity, especially if a large rain event occurs immediately after the fire, and before new vegetation has established a new hold in the existing soil. This can ultimately cause major flooding in the lower elevation states. Equally disturbing, the first few years after a bark beetle epidemic (while red needles are still clinging to the trees) can cause an increase in fire danger, and large wildfires have generally followed past bark beetle epidemics. We currently can expect to see the same. After needle fall, fire danger declines until the dead trees begin to fall and increase large fuel loadings on the ground. If a wildfire were to occur in this situation, greater soil heating could occur, potentially causing soil sterilization (hydrophobic soils) and causing re-vegetation to occur at a much slower rate. For those families who live and/or make their living in the mountain communities, it would mean an end to their way of life, further imperiling our weakened economy. While it may not have an obvious initial effect on the major population areas, we have to ask ourselves: “Where are the animals of the forest going to live when the forests are gone?”

The Pinecone Project has put together a program that will enable you to personally do something constructive to help save our precious forests, and at the same time leave behind a lasting legacy for your children and grandchildren. Our goal is not the usual one: to simply seek donations (although we won’t turn them away). Rather, our program is both fun and fulfilling, and will save what’s left of our forests and replant the rest!

We won’t see the magnificent forests again

in our lifetime unless there is

some direct intervention now!

Click here to learn more….

*Please Note: Fire is an integral part of western ecosystems; in fact, many species, such as lodgepole pine and aspen, are adapted to regenerate with and after a fire. Lodgepole pine has serotinous cones (meaning they are closed with a waxy substance) which open under the intense heat of a wildfire, scattering new seeds onto the freshly exposed mineral soil, allowing new regeneration to become established. A great example of this is Yellowstone National Park after the 1988 fires that ‘devastated’ the park; a carpet of new trees can be seen over the majority of burned area. Aspen is a clonal species, meaning it regenerates from root sprouts (called suckers or suckering) more commonly than from seed. When a fire comes through and kills the above-ground portion of the tree, the chemical inhibition that suppresses the sprouting response in the connected root system is released, and new trees sprout as soon as a year or two after the fire. Within a few years, they can exceed four to six feet tall. For other species, like Engelmann spruce, it takes longer for regeneration. Spruce seeds, while windborne, generally do not travel more than a hundred feet or so from their parent trees. In many cases, it takes many, many years for spruce regeneration to establish after a large-scale wildfire or beetle epidemic. Nonetheless, no one likes to see a red-needled or gray forest, and we certainly don’t want to see a large forest fires consuming what is left of the remaining green trees. For those families who live, and/or make their living, in the mountain communities, it can mean a reduction in their quality of life, can exacerbate lung-related health issues, and have an associated impact on their pocketbooks because of reduced tourism and business coming into their area.

Pinecone Project – Adopt a Tree Program

Pinecone Project – Adopt a Tree Program